How To Write Your Own Python Documentation Generator

In my early days with Python, one of the things that I really liked was using the built-in help function to examine classes and methods while sitting at the interpreter, trying to determine what to type next. This function imports an object and walks through its members, pulling out docstrings and generating manpage-like output to help give you an idea of how to use the object it was examining.

The beauty about it being built into the standard library is that with output being generated straight from code, it indirectly emphasizes a coding style for lazy people like me, who want to do as little extra work as possible to maintain documentation. Especially if you already choose straight forward names for your variables and functions. This style involves things like adding docstrings to your functions and classes, as well as properly identifying private and protected members by prefixing them with underscores.

Help on class list in module builtins:

class list(object)

| list() -> new empty list

| list(iterable) -> new list initialized from iterable's items

|

| Methods defined here:

|

| __add__(self, value, /)

| Return self+value.

...

| __iter__(self, /)

| Implement iter(self).

...

| append(...)

| L.append(object) -> None -- append object to end

|

| extend(...)

| L.extend(iterable) -> None -- extend list by appending elements from the iterable

|

| index(...)

| L.index(value, [start, [stop]]) -> integer -- return first index of value.

| Raises ValueError if the value is not present.

...

| pop(...)

| L.pop([index]) -> item -- remove and return item at index (default last).

| Raises IndexError if list is empty or index is out of range.

|

| remove(...)

| L.remove(value) -> None -- remove first occurrence of value.

| Raises ValueError if the value is not present.

...

| ----------------------------------------------------------------------

| Data and other attributes defined here:

|

| __hash__ = None

The help function is actually using the pydoc module to generate its output, which is also runnable from the command line to produce a text or html representation of any importable module in your path.

A little while ago I needed to write more detailed, formal, design documentation and — being a fan of Markdown — I decided to play around with mkdocs to see if I could get what I was looking for. This module makes it easy to turn your markdown text into nicely styled web pages and can serve them up as you make changes before publishing to an official location. It comes with a template for readthedocs and even provides an easy command line interface to push your changes into GitHub Pages if you wish to go down that route.

Having completed my initial batch of text describing design decisions and considerations, I wanted to add details on the actual interface methods I was developing and exposing to the other modules in the project. Since I already wrote the definitions for most of those functions, I intended to automatically generate the reference pages from my source, and I wanted it in markdown so it could render into html along with the rest of my documentation whenever I ran mkdocs.

However, it turns out there is no default way of generating markdown from source with mkdocs, but there are plugins. After googling and researching a bit more, I was not content with the projects or plugins I found — lots of things are out of date, not maintained, or the output was just not what I was looking for — so I decided to write my own. I thought it would be another interesting foray into learning more about a module I used a little while ago when building a debugger for one of my previous articles (see Hacking together a Simple Graphical Python Debugger): the inspect module.

“The inspect module provides several useful functions to help get information about live objects… ” — Python Docs

Inspect this!

Originating from the standard library, inspect not only lets you look at lower level python frame and code objects, it also provides a number of methods for examining modules and classes, helping you find the items that may be of interest. It’s what pydoc uses to generate the help files mentioned previously.

Browsing through the online documentation, you’ll find a number of methods relevant to our adventure. The most important ones being getmembers(), getdoc() and signature(), as well as the many is... functions that serve as filters to getmembers. With these we can easily iterate through functions, including distinctions between generators and coroutines, and recurse into any classes and their internals as needed.

Importing the code

If we’re going to inspect an object, no matter what it is, the first thing to do is provide a mechanism with which to import it into our namespace. Why even talk about imports? Depending on what you want to do, there’s a number of items to worry about, including virtual environments, custom code, standard modules and reused names. Things can get confusing, and getting it wrong can lead to some frustrating moments trying to figure things out.

We do have a few options here, the more complete one being a reuse of safeimport() directly from pydoc, which takes care of a number of special cases for us and raises a pretty ErrorDuringImport exception when things break. However, it’s also possible to simply run __import__(modulename) ourselves if we have more control over our environment.

Another item to keep in mind is the path from which code executes. There may be a need to sys.path.append() a directory in order to access the module we’re looking for. My use case is to execute from the command line and within a directory that’s in the path of the module being examined, so I added the current directory to sys.path, which was enough to take care of the typical import path issues.

Keeping this in mind, our import function would look something like this:

def generatedocs(module):

try:

sys.path.append(os.getcwd())

# Attempt import

mod = safeimport(module)

if mod is None:

print("Module not found")

# Module imported correctly, let's create the docs

return getmarkdown(mod)

except ErrorDuringImport as e:

print("Error while trying to import " + module)

Deciding on the output

Before continuing on, you’ll want to have a mental picture of how to organize the markdown output being generated. Do you want a shallow reference that does not recurse into custom classes? Which methods do we want to include? What about built-ins? Or _ and __ methods? How should we present function signatures? Should we pull annotations?

My choices were as follows:

- One

.mdfile per run with information generated from recursing into any child classes of the object being inspecting. - Only include custom code that I’ve created, nothing from imported modules.

- The output must be identified with 2nd level markdown headers (

##) per item. - All headers must include the full path of the item being described

(

module.class.subclass.function) - Include the full function signature as pre-formatted text.

- Provide anchors for each header to easily link into the docs, as well as within the docs themselves.

- Any function that starts with

_or__is not intended to be documented.

Putting it all together

Once the object is imported, we can get to work inspecting it. It’s simply a matter of performing repeated calls to getmembers(object, filter) where the filter is one of the helper is functions. You’ll be able to get pretty far with isclass and isfunction, but the other relevant ones will be ismethod, isgenerator and iscoroutine. It all depends on whether you want to write something generic that can handle all the special cases, or something smaller and more specific the source code. I stuck with the first two because I knew I didn’t have anything else to worry about and split things into three methods to create the formatting I wanted for modules, classes and functions.

def getmarkdown(module):

output = [module_header]

output.extend(getfunctions(module))

output.append("***\n")

output.extend(getclasses(module))

return "".join(output)

def getclasses(item):

output = list()

for cl in inspect.getmembers(item, inspect.isclass):

if cl[0] != "__class__" and not cl[0].startswith("_"):

# Consider anything that starts with _ private

# and don't document it

output.append(class_header)

output.append(cl[0])

# Get the docstring

output.append(inspect.getdoc(cl[1]))

# Get the functions

output.extend(getfunctions(cl[1])))

# Recurse into any subclasses

output.extend(getclasses(cl[1]))

return output

def getfunctions(item):

for func in inspect.getmembers(item, inspect.isfunction):

output.append(function_header)

output.append(func[0])

# Get the signature

output.append("\n```python\n")

output.append(func[0])

output.append(str(inspect.signature(func[1])))

# Get the docstring

output.append(inspect.getdoc(func[1]))

return output

When formatting a large body of text and interweaving with some programmatic code, I tend to prefer to stick it all as separate items in a list or tuple and "".join() the output to put it all together. At the time of this writing, it’s actually faster than .format and % based interpolation. However, the new string formatting coming with python 3.6 will be faster than this and more readable.

As you can see, getmembers() returns a tuple with the name of the object in the first position and the actual object in the second, which we can then use to recurse through the object hierarchy.

For each one of the items retrieved, it’s then possible to pull docstrings and comments with getdoc() or getcomments(). For every function we can use signature() to get a Signature object that represents its positional and keyword arguments, their default values and any annotations, providing us with the flexibility of generating fairly descriptive and well styled text that helps our users understand the intent of the code we’ve written.

Other considerations and unintended consequences

Please note that the code above is just sample code only meant to give you an idea of what the final product should look like. There are quite a few more considerations to keep in mind before finalizing things:

- As is,

getfunctionsandgetclasseswill show ALL functions and classes imported in the module. This includes builtins, as well as anything from external packages, so you’ll have to filter that for-loop some more. I wound up using the__file__property of the module that contains whatever item I’m inspecting. In other words, if the item is defined in a module that exists within the path in which I’m executing, then include it (useos.path.commonprefix()) - There are some gotcha’s with file paths, import hierarchy and names. Like when you import moduleX into a package through init.py, you’ll be able to access its functions as package.moduleX.function, but the full name — the one returned by moduleX.name — will be package.moduleX.moduleX.function. You may not care, but I did, so it’s something to keep in mind when iterating through things.

- You’ll import classes from

builtinsand anything from there does not have__file__, so check for that if you put any filtering in place like described above. - Because this is markdown and because we’re simply importing docstrings, you can include markdown in your docstrings and it will appear in the page all nice and pretty. However, this means that you should take care to properly escape the docstring so it doesn’t break the HTML generated.

Sample output

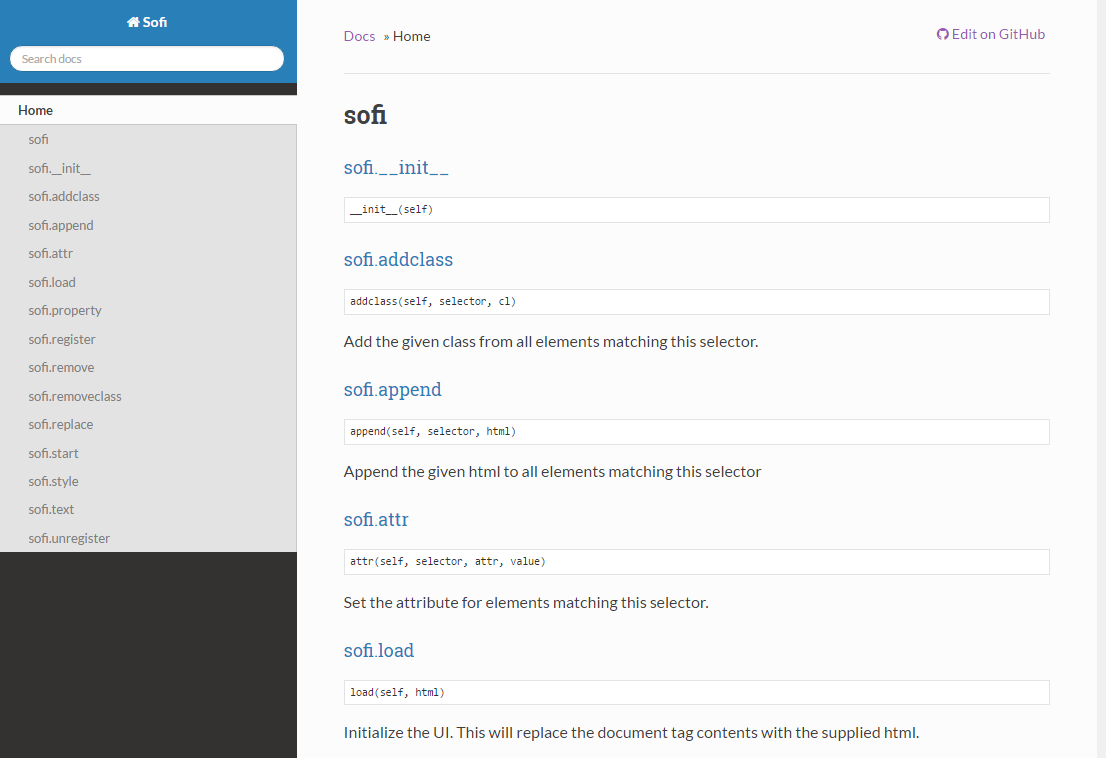

I ran my generator over the sofi package — the sofi.app module to be precise — and here’s the markdown it created.

# sofi<a name="sofi"></a>

<a name="sofi.__init__"></a>

### [sofi](#sofi).\_\_init\_\_

````python

__init__(self)

````

<a name="sofi.addclass"></a>

### [sofi](#sofi).addclass

````python

addclass(self, selector, cl)

````

Add the given class from all elements matching this selector.

Below is a sample of the final product (excluding function annotations) after running it through mkdocs to produce a readthedocs themed page.

As I’m sure you already know, using these mechanisms for automatically generating documentation leads to complete, accurate and up-to-date information on your modules that’s easy to maintain and edit as you write the code, instead of after the fact. I strongly encourage everyone to give it a shot.

Before closing, I’d like to take a step back and mention that mkdocs is not the only documentation packageout there. There are other well known and widely used systems like Sphinx (which mkdocs is based on) and Doxygen, both of which already do what we discussed here. However, as always, I wanted to go through the exercise in order to learn more about Python internals and the tools that come with it.